A proper understanding of antennas requires familiarity with electromagnetics, circuit theory, electronics and signal processing.

Candace Suriano, Ph.D., Suriano Solutions

John Suriano, Ph.D., Nidec Motors, Auburn Hills, MI, USA

Tom Holmes, Agilent Technologies, Tipp City, OH, USA

Qin Yu, Alcatel-Lucent, Columbus, OH, USA

How does an antenna pick up a signal and convert it to something useful to a receiving circuit? What is the current path for the signals received or transmitted from an antenna? Why are there different types of antennas, and why do they have different shapes? What are the standard engineering terms associated with antenna technology? How are signals from antennas amplified?

It is the starting point for understanding many EMC requirements and test procedures and for resolving compliance issues. The basics of antennas can be deduced from fundamental principles of electromagnetics and electric circuits. Even a rudimentary understanding can prove to be invaluable in solving EMC problems.

How Do Antennas Detect Signals?

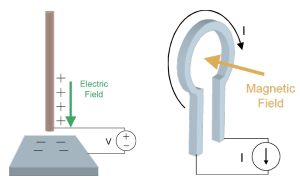

Antennas have two complementary functions: converting electromagnetic waves into voltage and current used by a circuit, and converting voltage and current into electromagnetic waves which are transmitted into space. Signals are transmitted through space by electromagnetic waves consisting of electric fields measured in Volts per meter and magnetic fields measured in Amps per meter. Depending on the type of field being detected, the antenna takes on a particular construction. Antennas designed to pick up electric fields, like the antenna of Figure 1(a), are made with rods and plates while antennas made to pick up magnetic fields, as in Figure 1(b), are made from loops of wire. Sometimes parts of electric circuits may have characteristics that unintentionally make them antennas. EMC is concerned with reducing the probability of these unintentional antennas injecting signals into their circuits or influencing other circuits.

Consider the antenna of a car radio. As the electric field (V/m) hits the antenna it impresses a voltage along its length (m*V/m = V) relative to ground. The receiver detects the voltage between the antenna and ground. Another way to think of this type of antenna is as one lead of a voltmeter measuring the potential in space. The other lead of the voltmeter is the ground of the circuit.

What is the Significance of an Antenna’s Shape?

Some antennas are made of loops of wire. These antennas detect the magnetic field rather than the electric field. Just as a magnetic field through a coil of wire is produced by the current in that coil, so too a current is induced in a coil of wire when a magnetic field goes through that coil. The ends of the loop antenna are attached to a receiving circuit through which this induced current flows as the loop antenna detects the magnetic field. Magnetic fields are generally directed perpendicular to the direction of their propagation so the plane of the loop should be aligned parallel to the direction of the wave propagation to detect the field.

Some types of electric field antennas are biconical, horn, and microstrip. Generally, antennas that radiate electric fields have two components insulated from each other. The simplest electric field antenna is the dipole antenna, whose very name implies its two-component nature. The two conductor elements act like the plates of a capacitor with the field between them projecting out into space rather than being confined between the plates. On the other hand, magnetic field antennas are made of coils which act as inductors. The inductor fields are projected out into space rather than being confined to a closed magnetic circuit. The categorization of antennas in this way is somewhat artificial, however, since the actual mechanism of radiation involves both electric and magnetic fields no matter what the construction.

How do Antennas Form and Radiate Electromagnetic Fields?

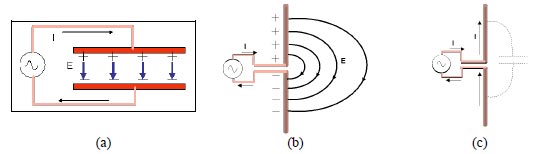

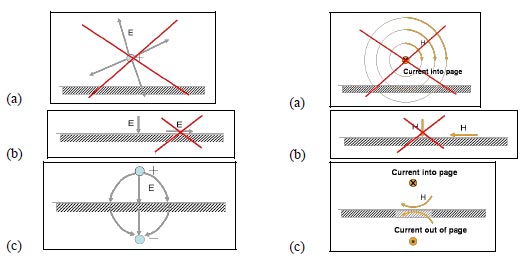

As previously mentioned, electric field antennas can be related to capacitors. Consider a simple parallel plate capacitor shown in Figure 2(a). The electric field that occurs when a charge is placed on each of the plates is contained in between the plates. If the plates are spread apart so that they lie in the same plane, the electric field between the plates extends out into space. The same process occurs with an electric field dipole antenna as shown in Figure 2(b). Charges on each part of the antenna produce a field into space between the two halves of the antenna. There is an intrinsic capacitance between the two rods of the dipole antenna as shown in Figure 2(c). Current is required to charge the dipole rods. The current in each part of the antenna flows in the same direction. Such current is called antenna mode current. This condition is special because it results in radiation. As the signal applied to the two halves of the antenna oscillates, the field keeps reversing and sends out waves into space.

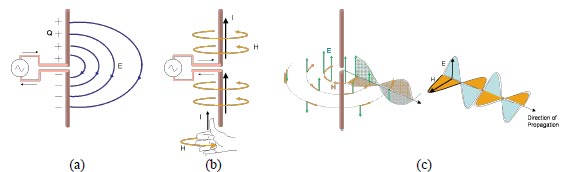

The charge and current on the dipole create fields that are perpendicular to each other. The electric field, E, flows from the positive charge to the negative charge placed on the elements by voltage applied to the antenna as shown in Figure 3(a). Charging current applied to the antenna makes a magnetic field, H, that circulates around the wire according to the right hand rule as shown in Figure 3(b). God made it so that when electrons move along the wire a magnetic “wind” is produced which circulates around the wire. Directing one’s right thumb in the direction of the current flow, the fingers wrap around the wire in the direction of the magnetic field. The circulation of this magnetic field results in inductance of the antenna. The antenna is therefore a reactive device having both capacitance from the charge distribution and inductance from the current distribution.

As shown in Figure 3(c), the E and H fields are perpendicular to each other. They spread out into space from the antenna in a circular fashion. As the signal on the antenna oscillates, waves are formed. Transverse Electromagnetic (TEM) waves are produced in which E and H are perpendicular to each other. The antenna can also convert a TEM wave back into current and voltage by something called reciprocity. The antenna has complementary behavior when sending and receiving.

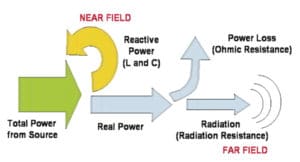

The condition of antenna radiation is shown in Figure 4. The reactive components of the antenna store energy in the electric and magnetic fields surrounding the antenna. Reactive power is exchanged back and forth between the supply and the reactive components of the antenna. Just as in any L-C circuit where the voltage and current are always 90° out of phase, so too with an antenna the E field (produced by voltage) and the H field (produced by current) are 90° out of phase if the resistance of the antenna is neglected. In an electric circuit, real power is delivered only when the load has a real component to its impedance that causes a component of the current and voltage to be in-phase. This circumstance also holds true with antennas. The antenna has some small resistance so there is a component of real power delivered that is dissipated in the antenna. For radiation to occur, E and H fields must be in-phase with each other as shown in Figure 3(c). With the antenna acting as both a capacitance and an inductance, how can this radiation take place? The in-phase components are the result of propagation delay. The waves from the antenna do not instantly form at all points in space simultaneously, but rather propagate at the speed of light. At distances far away from the antenna, this delay results in a component of the E and H fields that are in phase.

Thus, there are different components of the E and H fields that comprise the energy storage (reactive) part of the field or the radiated (real) part. The reactive portion is dictated by the capacitance and inductance of the antenna and exists predominately in the near field. The real portion is dictated by something called radiation resistance, caused by the propagation delay, and exists at large distance from the antenna in the far field. Sometimes receiving antennas, such as those used in EMC testing, may be placed so close to the source that they are influenced more by the near field effects than the far field radiation. In this case, the receiving and transmitting antennas are coupled by capacitance and mutual inductance. The receiving antenna thus acts as a load on the transmitter.

How Does the Antenna Impedance Change with Frequency?

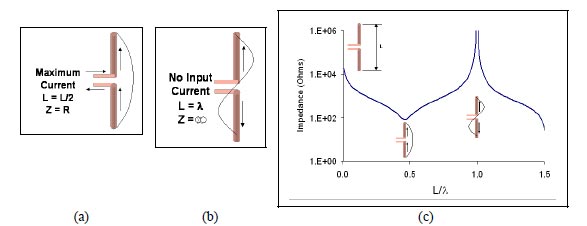

Antenna impedance is a function of frequency. The current and charge distribution on the antenna change with frequency. The current on a dipole is generally shaped as a sinusoidal function of position on the antenna as dictated by the frequency. Since the wavelength of a signal is dependent on the frequency, at certain frequencies the antenna length is equal to key fractions of a wavelength. The current on a dipole for frequencies resulting in ½ and 1 wavelength is shown in Figure 5(a) and 5(b), respectively. At ½ wavelength, the current from the source is maximal. The input impedance of the antenna at this frequency is therefore minimum, equivalent to the resistance of the antenna (actual + radiation resistance). At a frequency that has a wavelength the same as the antenna length, the current from the source is zero; and therefore, the input impedance is infinite. A plot of the impedance vs. frequency is shown in Figure 5(c).

Do Antennas Radiate in All Directions?

The power from an antenna radiates in a pattern that may not be uniform in all directions. To characterize the antenna gain, the ratio of the power radiated in a given direction to the power density if radiation occurred uniformly in all directions (distributed over the surface of a sphere) is used. For a dipole antenna, most of the power radiates in the direction perpendicular to the axis of the antenna as shown in Figure 3. The directivity of an antenna is the gain in the direction of the maximum power, which is the direction perpendicular to the axis of a dipole. Gain is measured in dBi=10*log(Gain).

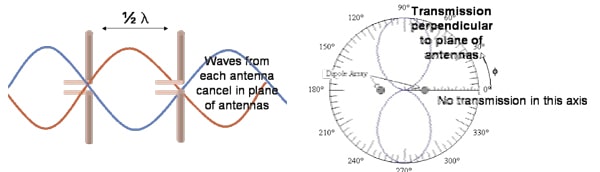

The three- or two-dimensional radiation pattern from an antenna is also called a power pattern, power plot, or power distribution. It visually illustrates how an antenna receives or transmits in a certain range of frequencies. It is normally plotted for the far field. An antenna radiation pattern is primarily affected by the geometry of the antenna. It is also affected by the surrounding landscape or by other antennas. Sometimes multiple antennas are used in an antenna array to affect directivity. As shown in Figure 6(a), two antennas fed by the same source can be used to cancel the fields in the plane of the antennas if they are spaced by ½ wavelength. The top view of this arrangement is shown in Figure 6(b) with a sketch of the power pattern.

Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: What is the Importance of Reflections?

When we look into a mirror,we see the effect of reflections of electromagnetic radiation. Why do waves bounce off of conductive surfaces? What is the result of these reflections on radiation? The basis for reflections is the boundary condition of the fields on the surface of a conductor. Boundary conditions for E and H fields are shown in Figure 7. Inside the conductor, charges are free to move when influenced by electric fields and current is induced by time-varying magnetic fields. A charge nearby the conductor causes charges to migrate on the conductor surface. Any tangential component of the E field would cause the charges to move until the tangential component of E is zero. The resulting effect is equivalent to the image, or virtual charge, located below the conductor surface shown in Figure 7(c). The image isn’t real, but represents the charge that would cause an equivalent effect to the actual result.

A magnetic field that is time-varying induces a current in the perfect conductor. The current opposes the magnetic field so that no normal component can penetrate the conductor surface. Thus the current image shown in Figure 7(c) causes the resulting normal component of H to disappear at the surface.

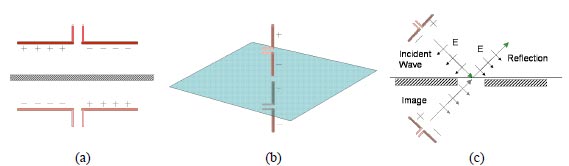

The effect of the image is very important because antennas are often nearby conductive surfaces such as the Earth, or the sheet metal of a car or airplane, or the ground plane of a circuit board. The fields that radiate into space are the sum of those from the antenna and those from the image. If we consider the E-field from a dipole, it is easy to see the effect. In Figure 8(a) a dipole parallel to conductor is shown with its image. When the dipole is perpendicular to the ground plane, an image of the dipole with inverted charge exists below it—as shown in Figure 8(b). In these two examples, the field at some point in space is the sum of the fields from the dipole and its image. When the field radiating from a dipole hits the conductor, as shown in Figure 8(c), the reflection can be interpreted as the wave from the image.

How Are Signals From Antennas Conditioned and Amplified?

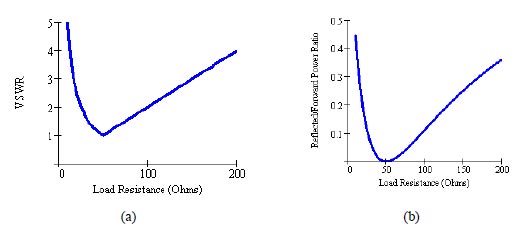

Antennas are connected to transmitters or receivers through transmission lines. Since the antenna impedance is not a constant function of frequency, it cannot be matched to the transmission line at all frequencies. When the antenna impedance does not match the impedance of the transmission line (usually 50 W or 75 W), reflections are formed at the connection to the antenna. Waves that come from the source are reflected back down the transmission line reducing the ability to transmit power. The VSWR, voltage standing wave ratio, is a measure of the mismatch. VSWR is the ratio of the maximum voltage to minimum voltage on the transmission line. With an impedance mismatch, the VSWR is greater than one, indicating the presence of reflections. As the impedance at the end of the transmission line becomes higher—approaching open circuit, the VSWR approaches infinity, indicating that all the power is reflected. This situation is similar to the incidence of a light beam at an interface between two media, such as air and water, in which some light is reflected and some goes into the water. VSWR reduces the amount of power transmitted to the antenna or reduces the signal from the antenna when it is used to receive signals. The change in VSWR and the proportion reflected are shown in Figure 9(a) and 9(b), respectively, for a 50-W system, in which the load resistance is varied.

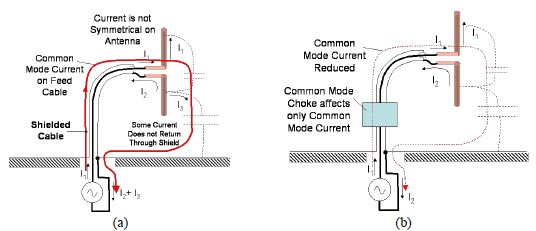

Another problem with connecting to antennas is signal unbalance caused by a ground plane. Figure 10(a) shows a dipole antenna connected to a source through a shielded cable. The shield is connected to the ground plane. Parasitic capacitance between the antenna and the ground plane causes some current to flow through the ground plane rather than through the shield. When this occurs, the current on the antenna is unbalanced, and the antenna loses efficiency. To correct this imbalance, a device called a balun (balanced to unbalanced) is used. A simple type of balun is shown in Figure 10(b). Here, the balun is comprised of a ferrite cylinder (bead) placed over the coaxial cable. The ferrite increases the impedance only for the common mode current and has no effect on the normal differential mode current in the cable. Consequently, the current that causes the unbalance is reduced, improving the operation of the antenna. For receiving antennas, the incoming signal may induce current on the shield that causes the unbalance. The ferrite bead reduces the current on the shield.

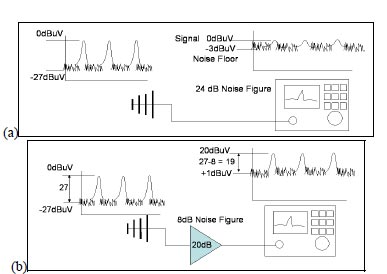

Antennas are used to receive very small signals. It is therefore often necessary to use an amplifier to increase the signal-to-noise ratio. The thermal noise floor of the environment, if detected by a 9-kHz bandwidth, is approximately –27 dBuV (-134 dBm). However, when signals are processed and amplified to useable levels, noise is introduced. The noise figure of an amplifier is defined as the difference between its noise floor and the ambient noise of the environment. Consider an antenna picking up a signal that is only 0 dBuVas shown in Figure 11(a). The signal may be 27 dB above the ambient; but to a receiver with a 24-dB noise figure, the signal is only 3 dB above the noise floor. Thus, the signal-to-noise ratio is only 3 dB. A good amplifier can be used to increase this margin as shown in Figure 11(b). Here, a 20-dB amplifier raises the signal level from 0 dBuV to 20 dBuV. The amplifier also raises the ambient by 20 dB to –7 dBuV. Since the amplifier has an 8-dB noise figure, it then adds another 8 dB to the ambient making it +1 dBuV. The noise floor of the receiver (-3 dBuV) is below this figure and thus does not affect the result. The new signal-to- noise ratio is 19 dBuV.

SUMMARY

A proper understanding of antennas requires familiarity with electromagnetics, circuit theory, electronics, and signal processing. Such knowledge is indispensable to the EMC engineer who must interpret test results, improve accuracy and sensitivity of tests, and suggest ways to eliminate unintentional antennas from product designs.

REFERENCES

[1] W. L. Weeks, Antenna Engineering, McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1968

[2] William H. Hayt, Jr., Engineering Electromagnetics, McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1981

[3] Warren L. Stutzman and Gary A. Thiele, Antenna Theory and Design, Second Edition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1998.

[4] Clayton R. Paul and Syed A. Nasar, Introduction to Electromagnetic Fields, McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, 1982.

[5] “Fundamentals of RF and Microwave Noise Figure Measurements,” Agilent Application Note 57-1, Agilent Technologies

[6] Clayton R. Paul, Introduction to Electromagnetic Compatibility, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1992.