By Vinti Singh

As the electronics industry continues to expand, employment opportunities for EMC engineers continue to grow as well. Products are becoming increasingly complex, and compatibility issues are arising ever more frequently. With each new advancement, EMC engineering jobs around the nation become more important, and more secure.

Experienced EMC engineers, especially those with specialized knowledge, are in demand, and these plum positions are not pencil-pushing desk jobs. Today’s EMC engineers are getting hands-on in the lab and constantly having to stay on the cusp of rapidly progressing innovations. They told Interference Technology this challenging atmosphere is why their day’s work is so satisfying. Interference Technology received this feedback, and more, in its first nationwide salary survey of EMC/EMI engineers.

Interference Technology sent a survey to a list of more than 15,000 EMC, design, and test engineers, from July through August 2013. Several hundred people responded to the request.

The results indicate that overall, the engineers are mostly satisfied with their career choices and current positions and value the complex problem-solving challenges of the job.

“What a wonderful time to be a part of the compliance world, with every new wave of emerging technologies comes a new wave of compliance challenges,” a corporate manager from Georgia commented in the survey.

Of course, the ‘compliance world’ includes much more than just EMC regulations, with existing regulations on radiocommunications, telecommunications, product safety, restriction of hazardous substances, and – increasingly – sustainability (e.g. power efficiency, standby power, etc.), and in smaller companies one compliance engineer might have to deal with the lot.

Compared to just 20 years ago, a number of new industries have emerged in compliance, noted Dan Paulson, the CFO of Paulson and Clark Engineering, an engineering services provider in White Bear Lake, Minnesota.

“A lot of engineers are not even aware of all the applicable fields, and you have a lot of industries pulling from the same pool of candidates,” Paulson said.

Salaries at Paulson & Clark have stayed stable in recent years.

Robert Kado, the EMC department manager and senior technical specialist for Chrysler Group, observed the same trend in the EMC segment of the automotive industry. His lab is busy with research and development of Bluetooth technology, alternative powertrain, and wireless charging for smart devices.

“The trend is that it’s hard to find the right people,” Kado said. In mid-August, an opening in his department had remained unfilled for a month. The company has offered bonuses and steady salary increases to its EMC team for the last three or fours years, and so far that has seemed to be the key to retention.

“The trend is that it’s hard to find the right people,” Kado said. In mid-August, an opening in his department had remained unfilled for a month. The company has offered bonuses and steady salary increases to its EMC team for the last three or fours years, and so far that has seemed to be the key to retention.

Hiring experienced talent is even harder in non-metropolitan areas. Therefore, Jim Teune, the lead EMC engineer at Gentex, has tried a different strategy. Gentex is a leading supplier of automatic dimming rearview mirrors and lighting assist driver features to the automotive industry, and is based in Zeeland, Mich. He finds fresh graduates with some background in radio frequency and trains and grows them into experienced team members. He keeps turnover low by giving engineers challenges that are suited to their individual skill sets.

“It works for me,” Teune said. “They stick around longer. Plus they are productive and enthusiastic about their job.”

Slightly more than a quarter of respondents said they have been in their current positions for more than two decades. About a quarter of survey respondents said they have been in their current position for one to two decades. Almost 20 percent have been in their current position for five to 10 years.

Michael Oliver is the vice president of EMC/ electrical engineering for MAJR Products Corporation, an EMC shielding manufacturer in Saegertown, Penn. He has been with MAJR for 12 years, and says his peers in the field average close to a decade, and he has witnessed very little turnover.

It takes three to five years to become truly proficient in the EMC field, said Daryl Gerke, an EMC consultant who is a partner at Kimmel Gerke Associates, based in St. Paul, Minn. But about 90 percent of the concepts are applicable across the electronics industry, he added, which makes for a highly portable experience. Therefore, someone in the military field could easily transition to automotive or medical or consumer electronics. The biggest learning curve is in grasping the regulations and requirements specific to that segment. When an EMC engineer is laid off, it is not unusual for them to get another job offer in a day, or even an hour, Gerke explained.

But a career in EMC can be very much more satisfying than just compliance, says Keith Armstrong, an EMC consultant with Cherry Clough Consultants Ltd. in the UK. He says that using good EMC engineering from the start of an electronic product design project (e.g. in circuit design, component choice and PCB layout) helps achieve good signal integrity and power integrity more quickly, meaning the product gets to market quicker, functions better, costs less to manufacture and is more reliable in the field. So EMC compliance engineers who educate their designer colleagues in good EMC design can make a huge improvement to the financial performance of their employers.

Of the electrical engineers surveyed, 32 percent identified specifically as EMC engineers. Other respondents identified as electrical engineers, compliance engineers, design engineers, test engineers or otherwise tangential to the field.

Most respondents, about 70 percent, said they felt mostly or very secure in their current positions.

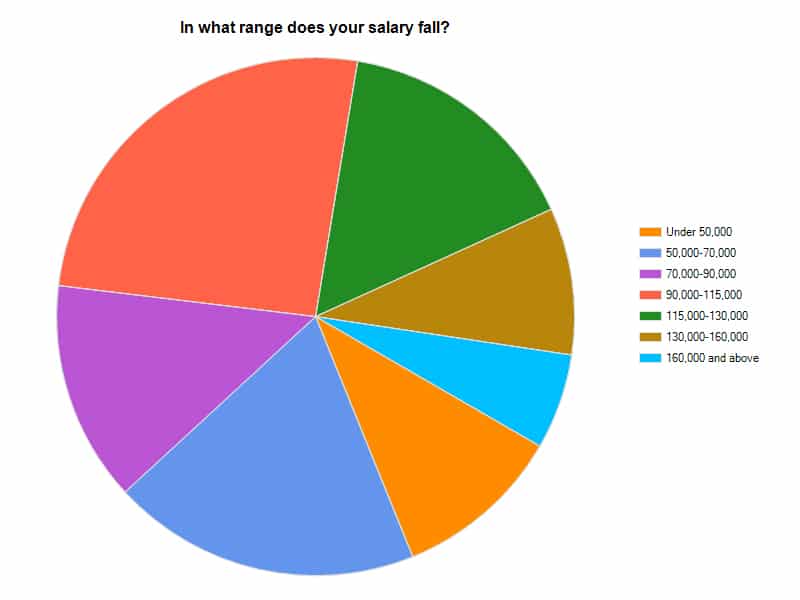

Twenty six percent of respondents said they make between $90,000 to $115,000. Thirty percent total of respondents total said they make more than $115,000, while about 45 percent total said they made less than 90,000.

Different sectors of EMC enter boom times depending regulatory rollouts, Gerke said. The medical sector saw such a boom in the early 1990s when the federal Food and Drug Administration and then the European Union began taking a special interest in medical devices. After 9/11, the military sector became especially active.

In 2010, the average salary for an electrical engineer with a bachelor’s degree was $87,180, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational Outlook Handbook. The average salary for an electronics engineer in that same year was $90,170. The labor statistics bureau estimates a 7 percent increase in electrical engineering jobs between 2010 and 2020 and estimates job openings due to growth and replacement needs will be close to 50,000.

About half of the respondents said they were mostly or very satisfied with their salary level. A little more than 20 percent said they were not very or not at all satisfied with their income.

About 55 percent of the survey takers said their salary and benefits were a major factor contributing to their job satisfaction.

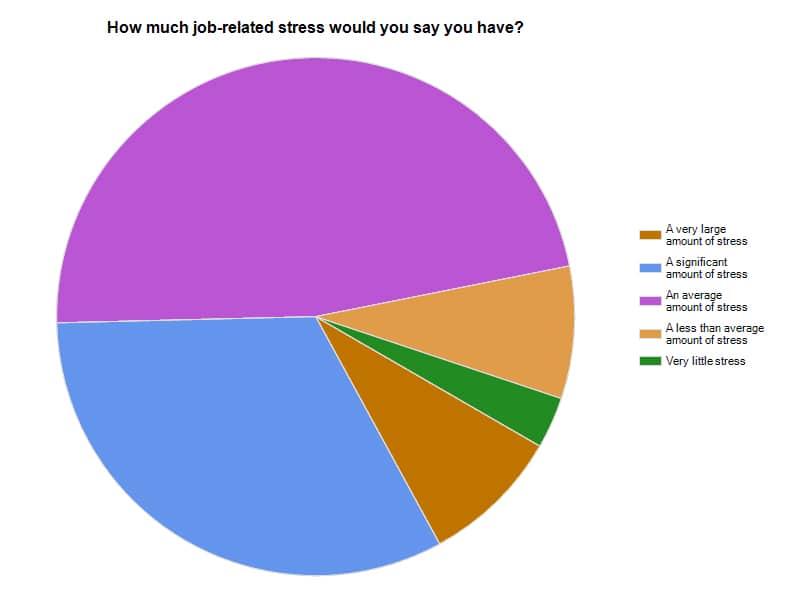

About half of the respondents reported feeling average amounts of stress, while about 40 percent said they felt a significant or very large amount of stress.

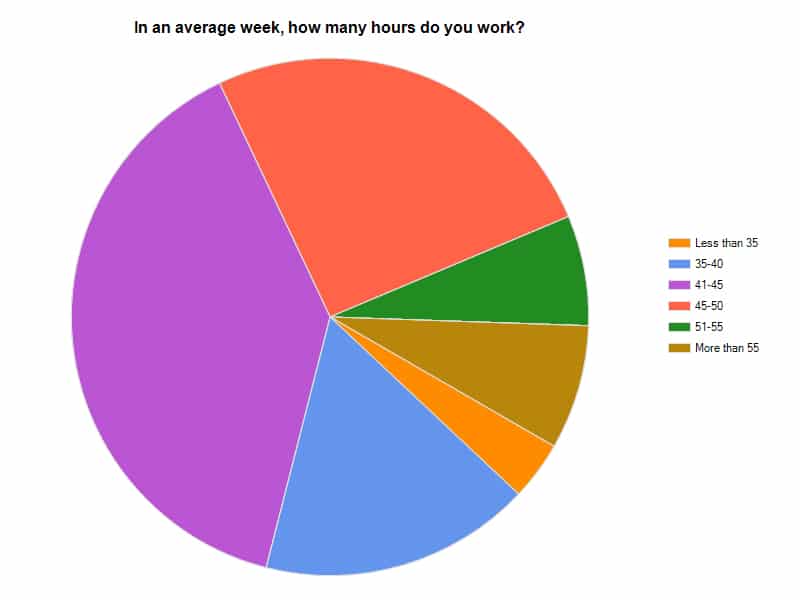

About 40 percent of the survey takers said they worked, on average, 41 to 45 hours a week. About 35 percent reported working 45 to 55 hours a week.

Some engineers commented stress resulted from having to coordinate with non-EMC colleagues or clients who do not understand EMC compliance needs.

“The field of compliance has changed drastically in the past few years,” said an EMC engineer in Massachusetts in the comments section of the survey. “The customer base has changed where the client is no longer a compliance engineer coming to test, but in fact a program manager. They have no ideas how to fix the EMI problems and rather skirt around product issues then simply fixing them.”

An EMC engineer from Colorado shared his frustration and said the business managers are the source of stress, as they don’t want to fix EMI issues, but rather “just BandAid and keep shipping the product.”

Stress also results from the fact that products are routinely designed and manufactured overseas, with all initial compliance checks performed there as well, he continued. Once the product reaches the States, it usually is checked again and often does not meet the standards. Design changes are hard to implement when it is hard to determine what the designer intended for the product to do.

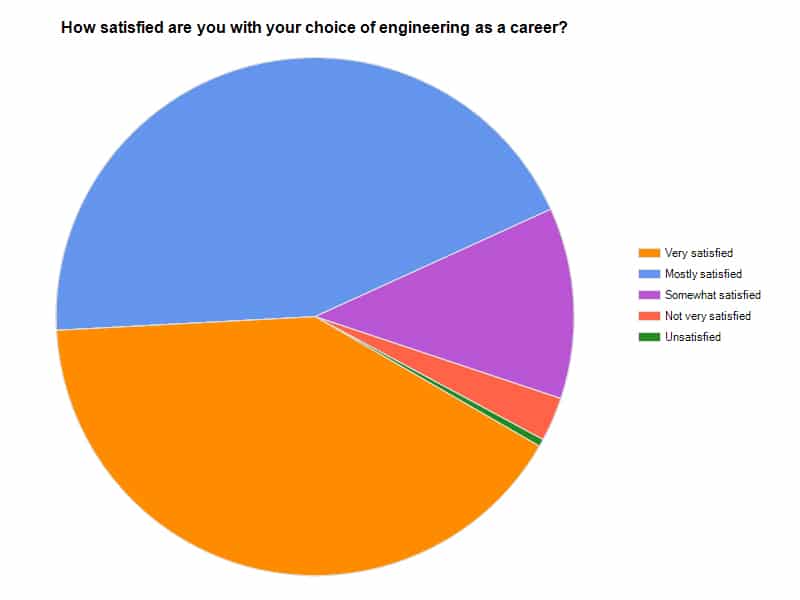

Most respondents said they were mostly satisfied or very satisfied with their choice of engineering as a career. Less than 15 percent reported that they were somewhat or not satisfied. None of the people surveyed said they were unsatisfied.

The biggest reason they attributed for their satisfaction was how often they were challenged and had to solve problems.

The survey takers commented the field is constantly expanding in its scope, and the variety of challenges encountered mean they are learning something new on a daily basis.

“I tell my guys, you are forever a student of EMC,” Teune said. “There’s always a changing standard or a new requirement. Our product evolves. Even though we might be using the same core design, we’re looking for cost saving measures.”

Opportunities to be creative and relationships with colleagues were other major contributing factors to job satisfaction, according to the survey.

“It’s a difficult job that requires the skills of a ‘rocket scientist’,” said an electrical engineer from Pennsylvania.

Company size and location were a major factor for almost 40 percent of respondents.

An EMC engineer from Hawaii described his job as, “a nice, fun interesting job nearby home, which is very positive.”

Similarly most respondents said they are mostly satisfied or very satisfied with their current positions. Almost 20 percent said they were somewhat satisfied and about 5 percent reported being unsatisfied.

“Private companies are so much nicer than public companies,” said an electrical engineer from Colorado. “You still have to work hard and are busy, but you do things because they need to be done and not because of some ignorant corporate objective, executive metric, or political jockeying.”

The majority of respondents said they were not looking for another position, but almost 40 percent of survey takers said they were passively searching for another job.

About 80 percent of respondents said they would recommend the field to a child or a friend.

“EMC is not a career for everybody, or even for every electrical engineer, but can be a very satisfying career for those with the right mind set,” said an EMC/EMI engineer from Missouri.

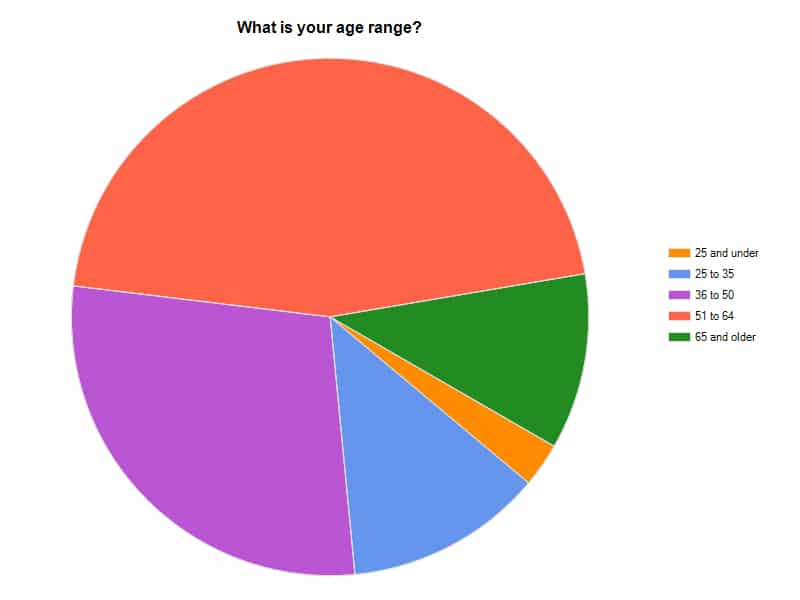

The majority (56 percent) of the respondents were 51 or older – approaching retirement age. About 40 percent were aged 25 to 50, and only about 3 percent were 25 and under.

“Five and a half years and I’m done [working],” said an engineering manager from Maryland, while an EMC engineer from Florida questioned, “Where is my replacement? Very few young folks qualify.”(To see Interference Technology’s article on up and coming student engineers, refer to the 2013 EMC Symposium Guide)

EMC consultant Daryl Gerke said he is in his 60s and his partner is on his 70s, but often feel like the “younger guys” at EMC conferences.

“I think there is a need for new fresh blood. Companies aren’t good at responding to that,” Gerke said.

When one of Gerke’s mentors was in his early 60s, he began pressing his employer to start grooming his replacement, but management didn’t heed his advice. At 65, he retired, and not long after, the company asked him to return as a consultant.

The survey results suggested the industry remains a male dominated one, as only slightly more than 7 percent of the respondents identified as female.

“Of the hundreds of EMC professionals I know, just three or four are women,” said Michael Oliver, “And the only women I know who do go into it are from India, China or other countries. I think the U.S. is really deficient in promoting EMC to women.” (Interference Technology has also published an article on women engineers, which ran in the 2013 EMC Directory and Design Guide)