Hiro dug into his soup.

“Did your dad fight in the war?”

Nodding, slurping up fat udon noodles, “Korea,” pausing and picking up a napkin to dab his chin. “My father was an engineer, highways and bridges, mostly in the North.” Hiro put down his napkin, laid his fast-food chopsticks across his bowl and picked up the chopstick wrapper. He meticulously folded the long paper in thirds and then lengthwise, making a little tent that he put on the table next to the tall can of Kirin beer we were sharing. “That was a long time ago.” He moved his chopsticks onto the paper rest and lifted the bowl to his lips, the steamy broth fogging his glasses. “Why do you ask?”

“Just curious.” It was a long time ago. So much has changed and the vast Pacific theatre of conflict in the mid-20th century is now crisscrossed by cargo ships and frequent-flyers. Japan, at the center of so much history in the region, figures prominently in technology trade, and recent regulatory changes have propped the door open—a little.

Hiro put down his bowl. “And now, U.S. manufacturers can get radios certified in the U.S.—but it is necessary to understand the process.” He took off his glasses and wiped them slowly with the dry end of the napkin.

“Can you tell me?”

Hiro put his glasses back on and pushed back from the table, gracefully straightening in his chair. “Hai.”

We sat at one of the quickie eateries that are clustered around the departure gates in Terminal 1 at Narita Airport—an East-West melting pot of travelers and outpost of diversity on an island of monolithic ethnicity.

Narita, opened in 1978 after much local protest and the lobbing of Molotov cocktails (!), is now an international hub, knitting together destinations such as Taipei, Beijing, San Francisco and Seoul. In the 70s, though, the construction of the airport was not a universally popular notion; years of protest preceded its opening and lasted well into its operations. In sharp contrast to the notion that Japan is a society of conformists, considerable resistance was mounted to try to block the construction of the airport, including protests and riots and, in the manner of the 60s and 70s crowd control: water cannons and tear gas.

But by the 1990s Narita became a key Asian hub and started accruing an interesting legacy. In 2001, Kim Jong-Nam, eldest son of North Korea’s King Jong-Il, was arrested at the airport with a fake passport. He apparently wanted to visit Disneyland Japan, but instead got a ride to China. His fake Dominican Republic passport failed to get him to “Space Mountain” and the jaunt allegedly cost him rule over his own “Magic Kingdom,” the anointment ultimately passing to his younger brother Kim Jong-Un.

We were just passing through—heading home—and Hiro was keeping us company during our extended layover after the APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation) Telecommunications meetings, a biannual event that links the 21 economies that form the trading group. Mutual Recognition Arrangements and Agreements (MRAs) are a hallmark of that work. Several such agreements, based on harmonized conformity assessment regimes, have facilitated much of the enormous trade between the U.S. and Asia. It is one of the reasons we’re spending a few hours in the large international airport outside of Tokyo.

Some 10 years after the implementation of the APEC Mutual Recognition Arrangement (MRA), trade between the 21 economies is around $9.4T (that’s Trillion with a capital “T”), according to the office of the U.S. Trade Representative, accounting for 44% of world trade. That is a lot of noodles.

The APEC Mutual Recognition Arrangement for conformity assessment of telecommunications equipment, the world’s first multi-lateral MRA, celebrated its 10th anniversary in July 2009. Developed by the APEC Telecommunications and Information Working Group (APEC TEL), the MRA benefits manufacturers by reducing the cost of getting a product approved and by reducing the time to market.

The MRA, a voluntary agreement, has fostered the expansion of technology and the access to competitively priced products amongst partner countries by reducing barriers to trade. Just as APEC continues to pursue its goals of “stability, security and prosperity,” the APEC TEL MRA Task Force continues to meet twice a year to discuss and develop additional arrangements, work out MRA issues and create bonds of friendship that reach across the oceans [1].

That beats fighting every time.

OPPORTUNITY FOR U.S. ORGANIZATIONS

The reality of U.S.-Japan trade in the past 40 years—since the mass proliferation of transistor-based devices—has been quite one-sided. One of the last access-issues to fall is the certification of wireless devices by U.S. Conformity Assessment Bodies (CABs). In contrast, CBs in the European Union have enjoyed this privilege since Valentine’s day 2003. (Singapore, too, has had an operating MRA since the early 2000s.)

So, for roughly the past seven years, European CBs (and implicitly European manufacturers) have had a greater access to the Japanese radio market than U.S. organizations. Of course, there are other economic realities that skew this benefit, such as the desirability of U.S. products on the Japanese market and other flavors of the U.S.-Japan cultural and business inter-relationship.

But now, at least, the U.S. is catching up.

Within the context of the APEC TEL MRA, Japan and the U.S. have implemented the MRA for wireless devices. The initial agreement was signed Feb. 16, 2007. Another three years passed before the technical and administrative details and criteria were hammered out.

Forged after a series of correspondences, meetings, queries, clarifications, discussions, understanding (and misunderstandings) between the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Japanese Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC), the U.S.-Japan MRA is now in full-force. Effective Nov. 1, 2010, NIST has been accepting applications from CABS that meet the specific criteria laid out under the agreement (for all of the bloody details, see [2]).

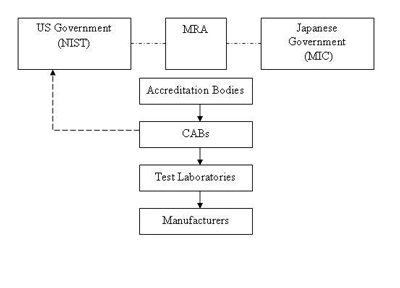

The agreement, like a difficult childbirth, was a bit painful and took some postpartum nursing, but it is finally standing and walking. In essence, the criteria require the CAB seeking approval to gain the necessary accreditation from a designated Accreditation Bodies, and ABs can now accept and process applications from Certification Bodies accredited to meet the international requirements in ISO Guide 65. The food chain is now established and looks a little like this:

Figure 2. Regulatory food chain.

Under the MRA, once a candidate CAB passes muster with its domestic “Designating Authority” or DA (NIST in the U.S.), then the DA advances the proposed CAB to the DA of the other country. There is a period of review and comment and, if the CAB is accepted, then the authority to issue certifications is granted by the process of a Joint Committee, which is composed of one or more members of each DA.

To understand why the agreement and final implementation were so stretched out, it is necessary to understand a few fundamental differences between U.S. and Japan practices. Some of the more interesting bits include challenges relating to differences in:

1) Laboratory/CAB Acceptance. An informal “Accreditation system” in Japan is the most different aspect between the systems. In contrast to the U.S., which relies on established mix of private and public-sector independent accrediting bodies, the Japanese system of accepting lab results was more on a relationship basis—not surprisingly given the customary and traditional internally focused system of kyoryoku (meaning “collaboration” and obliquely referring to a system of preference that makes it difficult for outsiders to break into Japan’s business circles.)

2) Regulatory structure difficulties in aligning methods and product certification schemes.

3) Test methods. Test procedures for measuring specific devices are difficult to identify and cross-reference.

Items 2) and 3) are essentially linked together. The method of organizing the regulations in the U.S. under the FCC system is essentially based on a Byzantine division of general device functionality and intended use mapped against frequency allocation; the requirements are, however, all covered under a single title (47) of the “Code of Federal Regulations”, the how-to manual of the United States federal government. The method of organizing the regulations in Japan is, at first, a little inscrutable and buried under a half-dozen or so ordnances and radio laws, with the technical requirements based on specific device type rather than general usage. This makes the mapping of well-understood methods of device assessment here (FCC) against there (MIC) quite, er, challenging.

A private sector organization and CB in Japan (DSP Research: http://www.dspr.co.jp/) has developed an English-language database that eases this issue. Still, it would be useful to understand a bit of kanji.

Note that there are similarities under both regimens for how non-licensed and licensed devices are handled. Non-licensed equipment (such as low power devices, cordless phones and the like) can be placed on the market without secondary licensing. Cellular phones, on the other hand, must have a “blanket license” that applies to the system operator; this is not unlike the U.S., where cell phones are licensed to the operator and the process is transparent to the end-user.

One of the requirements of the MRA is to demonstrate that a Conformity Assessment Body is approved to a scope that is equal to or greater than the requirements outlined in the MIC regulations. This bit of cross-referencing requires a deep dive into the methods for the devices, sorting through the technical requirements and demonstrating “competency by association.”

I WANT MY RADIO CERTIFIED. WHERE TO BEGIN?

For any type of produce certification, one asks the same questions: What Provisions? What Requirements? What Limits?

Any roadmap to certify a radio to Japanese law includes three main documents, starting with the Radio Law (Law No. 131 of May 2, 1950, as amended) which says that radios of a certain type (Specified Radio Equipment) must be certified. The Radio Law covers the usual administration and authority requirements, as well as spelling out a path for certifying equipment and operators. Other various topics include operation of coast guard stations and aeronautical stations and there are chapters on lawsuits and penal provisions. (Note that Terminal Equipment is covered by the Telecommunications Business Law—Law No. 86 Dec. 25, 1984, as amended. In short, the approval process is similar for wireless and wireless telephony.)

Article 38-2 of the Radio Law covers the requirements for Certification Bodies, to wit “…a person who wishes to conduct the business of certifying such radio equipment’s conformity with the technical regulations specified in the preceding Chapter may obtain registration from the Minister…[The Radio Law includes, by the way, requirements for maintaining decency and decorum on the air. George Carlin would certainly balk:

“Article 108: Any person who transmits a message with indecent contents by means of radio equipment or communications equipment under Article 100 paragraph (1) item (i) shall be guilty of an offense and liable to imprisonment with work for a period not exceeding two years or to a fine not exceeding one million yen.”

[Note that this is not your ordinary imprisonment, it is imprisonment with work—breaking rocks. This is where they get all the nice stone for their Zen gardens.]

Chapter 3 of the Radio Law is specific to radio equipment and this is where we dig into the details and how, ultimately, the MRA provides the bridge between the U.S. certification bodies (more properly: Conformity Assessment Bodies) and wireless certifications for Japan. NIST is now actively in the process of approving CABs for this process. As stated before, the private sector has existing capacity (under the APEC Tel MRA and the Japan-EU MRA).

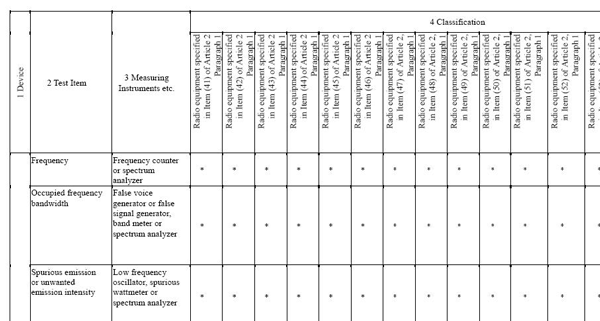

To get an approval, one must generate a report and demonstrate conformance (and submit to a Certification Body). To determine what data must be collected, it is necessary to refer to the ordnances that cover the specified equipment, notably the “Ordinance concerning Technical Regulations Conformity Certification of Specified Radio Equipment (aka Ordinance of the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications No. 37, 1981).” This document lays out the various types of equipment and what data are to be collected and what instrument is used to collect the data.

Table No. 1 (which covers eight pages) breaks down the action in a paragraph-by-paragraph cross-reference dependent on device function, providing the general quantity to be measured—“Frequency” and “Occupied Frequency Bandwidth”—and the type of instrumentation necessary. A fragment is shown in Figure 3 for illustrative purposes.

Figure 3. A fragment of Table No. 1 from the Radio Law.

By way of example, Article 2 (Specific Radio Equipment, etc.) calls out the frequency allocation and power limits for marine mobile equipment as follows:

“(1)-13 The radio equipment with an antenna power of 50 W or less which is used at a radio station for maritime mobile service using class A3E emissions of a frequency in a range of higher than 26.1 MHz to 28 MHz, higher than 29.7 MHz to 41 MHz, or higher than 146 MHz to 162.0375 MHz.”

For this specific equipment, referring to Table No. 1, the following data need to be collected:

Frequency, Occupied Bandwidth, Spurs, Deviation, Power, Overall Frequency Characteristics, Distortion…etc. Requirements also exist for the receiver: Spurious radiated emissions, Sensitivity, Passing bandwidth, Attenuation and Spurious response, Fluctuation of LO and overall distortion and noise.

Now that we know what data must be collected, the question becomes: what are the limits? The answer is to be found, in part, in the Radio Regulatory Commission Regulations No. 18, 1950. The 293-page document has the technical details, limits on power, use, and construction, viz “The high-frequency section and modulation section (except for the antenna system) shall not be capable of being opened easily.”

To figure out where the requirements are in this document, one starts at the table of contents and reads through the description in the “Conditions for Radio Equipment Classified by Service or Emission Class and Frequency Band.” This index is invaluable.

For example, Article 49.20 of No. 18 covers the requirements for low power spread spectrum devices operating in the ISM 2.4 GHz band, a pretty popular spot for WiFi, Bluetooth, etc.

These three critical documents can be found online: http://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/joho_tsusin/eng/laws_dt02.html

If you’re adept at reading Japanese, you can always download the original versions; it is a little tricky because the documents don’t have traditional title pages, at least in the English form.

To summarize,

The Radio Law (Law No. 131 of May 2, 1950) has the general requirements (akin to Part 2 of CFR47). Ordinance of the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications No. 37, 1981 contains the parameters to measure, and Radio Regulatory Commission Regulations No. 18, 1950 has the limits.

“So, Hiro, it’s really necessary to understand ordnances 37 and 18, right?”

He nodded, smiled and said, “And, maybe get a little help from your friends.”

United Flight 890 to Los Angeles now boarding Gate 8.

My friend polished off the last drops of soup and sat back, smiling.

“Ready to go?”

“Always. Arigato!”

REFERENCES

[1]” Fostering International Trade: Ten Years of MRA Success,” APEC, Sep. 2010, <http://www.apec.org/en/Press/Features/2010/0906_Fostering_International_Trade_Ten_Years_of_MRA_Success.aspx>.

[2] “Criteria for Designation of U.S. Conformity Assessment Bodies under the US-Japan Mutual Recognition Agreement,” NIST, Oct. 2010, <http://gsi.nist.gov/global/docs/mra/2010_10_01_Final_Criteria_for_CAB_Designation_to_Japan_V1_0.pdf>.

Mike Violette is founder and director of American Certification Body and president of Washington Laboratories. Violette oversees operations of ACB’s activities in the U.S., Asia and the EU and knows where to find decent sushi at Narita. He can be reached at mikev@acbcert.com.