Andreas Eberhard

Vice President Power Standards Lab

Immunity from voltage sags is vital for reliable operation of our ever-more-sophisticated electronic controls and equipment. Every electrical product should be able to ride through typical voltage sags, but in many cases the first sag test occurs after equipment is installed and in operation. Select the appropriate sag immunity specification and equipment compliance testing, and you’ll be glad you did.

Modern equipment can be sensitive to brief disturbances on utility power mains. Electrical systems are subject to a wide variety of power quality problems that can interrupt production processes, affect sensitive equipment, and cause downtime, scrap, and capacity losses. The most common disturbance, by far, is a “sag”: a brief reduction in voltage lasting a few hundred milliseconds.

Sags are commonly caused by fuse or breaker operation, motor starting, or capacitor switching, but they are also triggered by short-circuits on the power distribution system caused by such events as snakes slithering across insulators, trenching machines hitting underground cables, and lightning ionizing the air around high-voltage lines. Many utilities report that 80% of electrical disturbances originate within the user’s facility.

A decade ago, the solution to voltage sags was to try to fix them by storing enough energy somehow and releasing it onto the AC mains when voltage dropped. Some of the old solutions included uninterruptible power supplies (UPS), flywheels, and ferroresonant transformers.

More recently, engineers have realized that voltage sag is really a compatibility problem with at least two classes of solutions: You can improve the power or you can make the equipment tougher. The latter approach is called “voltage sag immunity,” and gets more important around the world.

Standards Developed

Three main primary voltage sag immunity standards are discussed in the following paragraphs: IEC 61000-4-11, IEC 61000-4-34, and SEMI F47. There are others in use—such as IEEE 1100, CBEMA, ITIC, Samsung Power Vaccine, international standards, and MIL-STD—but the first three seem to have the widest acceptance in the marketplace. (IEC is the International Electrotechnical Commission, SEMI is the Semiconductor Equipment and Materials Institute, CBEMA is the Computer Business Equipment Manufacturers Association, ITIC is the Information Technology Institute Council, and MIL-STD is the U.S. Defense Department’s specification.)

IEC 61000-4-11 and IEC 61000-4-34 are a closely related set of standards that cover voltage sag immunity. IEC 61000-4-11 Ed. 2 covers equipment rated at 16 amps per phase or less while IEC 61000-4-34 Ed. 1 covers equipment rated at more than 16 amps per phase. The latter was written after IEC 61000-4-11, so it seems to be more comprehensive.

SEMI F47 is the voltage sag immunity standard used in the semiconductor manufacturing industry, where a single voltage sag can result in the multi-million-dollar loss of product if a facility is not properly protected. The semiconductor industry has developed specifications for its manufacturing equipment and for components and subsystems in that equipment. Enforcement is entirely customer-driven in this industry, as semiconductor manufacturers understand the economic consequences of sag-induced failures and generally refuse to purchase new equipment that fails the SEMI F47 immunity requirement. SEMI F47 is currently going through its five-year revision and update cycle.

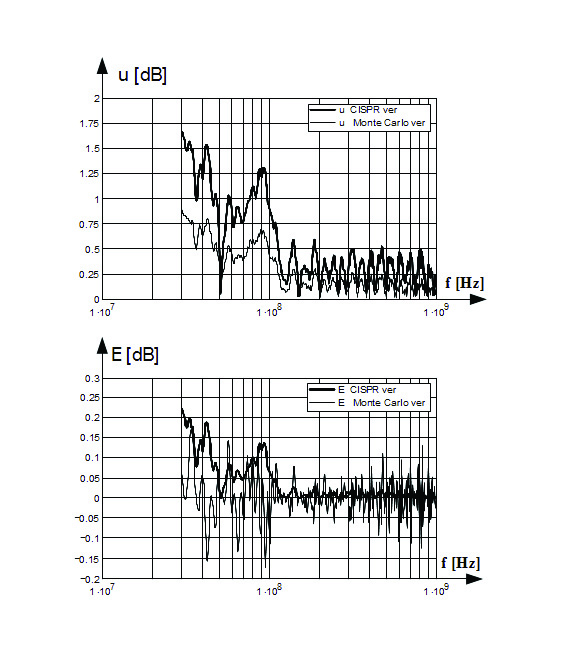

All three standards specify voltage sags with certain depths and durations for the equipment under test (EUT). For example, a specification may state 70% of nominal for 500 milliseconds. The percentage is the amount of voltage remaining, not the amount that is missing. Each standard specifies pass-fail criteria for EUT when a voltage sag is applied; the IEC standards have a range of pass-fail criteria, but the SEMI F47 standard is more explicit (photo 2).

A Different Kind of Testing

In contrast to most other emissions and immunity testing, voltage sag testing requires the engineer to control and manipulate all of the power flowing into the EUT. For smaller devices such as personal computers, this is not a great challenge. But for larger industrial equipment; perhaps rated at 480 volts three-phase at 200 amps per phase and an expected in rush current of 600 amps or more, the test engineer must be prepared for serious performance and safety challenges.

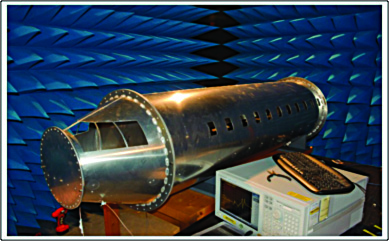

A voltage-sag generator is a piece of test equipment that is inserted between the AC mains and the EUT. It generates voltage sags of any required depth and duration. Some, like the PSL Industrial Power Corruptor, include pre-programmed sags for all of the IEC, SEMI or MIL standards.

Because a common EUT failure mechanism is a blown fuse or circuit breaker during the current inrush after a voltage-sag, the sag generator must be specified for delivering large peak currents – typically in the hundreds of amps. This peak current requirement in the IEC standards means that electronic amplifier AC sources generally can only be used for pre-compliance testing, not certification

Certain software, such as the sag immunity testing software from Power Standards Lab, comes with extensive safety checklists: some of the checklist items are obvious (who on the test team is trained in CPR?, Where is the closest fire extinguisher?) and some are less obvious (How do we get access to at least two upstream circuit breakers?, Where is the closest trash can?).

This kind of testing requires a fully-functional EUT, and someone who knows how to operate it. The only way to determine if an EUT is immune to the required voltage sags is to have it fully operating during the voltage sags; in many cases, the sags will need to be applied during different stages of EUT operation. Remarkably often, the EUT is not ready on time for voltage sag testing. Development work may need to be completed, or no one is available to operate the EUT, or the supplies to operate the EUT (raw materials, cooling water, compressed air, etc.) are not available, or the EUT software is broken. Test engineers should plan for these kinds of problems.

EUT failure mechanisms can be complicated, too, and the test engineer will be expected to help diagnose them. The built-in digital oscilloscopes in most sag generators will help, but the test engineer must figure out where to connect the channels to circuits inside the EUT.

Common failure mechanisms due to voltage sags

The most common failure mechanism is lack of energy. This can manifest itself in something as simple as insufficient voltage to keep a critical relay or contactor energized or something as complex as an electronic sensor with a failing power supply giving an incorrect reading, which would cause EUT software to react inappropriately (Figure 6).

The second most common failure mechanism, surprisingly, occurs just after the sag has finished. In such cases, all of the bulk capacitors inside the EUT recharge at once, causing a large increase in AC mains current. This increase can trip circuit breakers, open fuses, and even destroy solid-state rectifiers. Most design engineers correctly protect against this inrush current during power cycling, but many do not consider the similar effects of voltage sags. Be careful when the test procedure is developed; if you use a sag generator that lacks sufficient current capability it will incorrectly pass the equipment if there is insufficient current available to blow a fuse or trip a circuit breaker in a half-cycle.

Another common EUT failure mechanism occurs when a sensor detects the voltage sag and decides to shut down the EUT. In a straightforward example, a three-phase EUT might have a phase-rotation relay that incorrectly interprets an unbalanced voltage-sag as a phase reversal and therefore shuts down the EUT. A more atypical example would be if you had an airflow sensor mounted near a fan, it detected that the fan had slowed down momentarily, and the equipment software misinterpreted the message from this sensor as indicating that the EUT cooling system had failed. In this case, a software fan failure signal delay is the solution to improve sag immunity.

One more typical EUT failure mechanism involves an uncommon sequence of events. For example, in one case, a voltage-sag was applied to the EUT and its main contactor opened with a bang. But further investigation revealed that a small relay, wired in series with the main contactor coil, actually opened because it received an open relay contact from a stray water sensor. That sensor, in turn, opened because its small 24-VDC supply output dropped to 18 V during the sag. The solution was an inexpensive bulk capacitor across the 24-VDC supply.

Many other failure mechanisms can take place during voltage sags. The question to the test engineer will always be: How do we fix this problem? Usually, there is a simple, low-cost fix once the problem is identified.

A new embedded Power Quality Measurement Technology

There’s a new way to increase the reliability of products due to common power quality and voltage sag problems. How about making the product more intelligent – so it can react depending on severity of the voltage sag problem?

You will see more and more of such permanently installed Power Quality Monitors on a product level. This new embedded technology comes with the huge advantage that power quality problems and energy consumption can be evaluated directly within the product or machine. The new Power Quality Monitor (Photo 4) has the same functionality and features as the well-known expensive Power Quality Instruments. These are typically used on a facility level and are much too expensive, and, of course way too big, to integrate and design into products. Traditional power quality instruments have been designed with their own unique packaging. By packaging this new little power quality instrument (the “PQube”) in a standard 35mm DIN-rail circuit breaker package, installation is greatly simplified. The new trend is towards anembedded and intelligent power quality functionality. The PQube detects any kind of power problems on the AC lines and can communicate directly with the product, machine or facility personnel.

The version shown in Photo 4 has Ethernet connectivity (and includes a web server, an FTP server, and an e-mail generator), wireless radio connectivity, and a modem connection. However, it is optimized to function without connectivity – it can easily store a year’s data on a removable SD memory card.

By following the software model of a digital camera, the PQube requires absolutely no software. When you connect a digital camera to your computer, you immediately see the pictures in a folder on your disk drive. The same is true for power quality data in this application.

With the ever-increasing use of sophisticated controls and equipment in industrial, commercial, institutional, and governmental facilities; the continuity, reliability, and quality of electrical service has become extremely crucial to many power users. The power will hardly get better in the future, so the ultimate goal for any product manufacturer is to make its product immune to voltage sags. As all modern cars should be able to drive through regular bumps on the road, every electrical product should be able to ride-through any regular voltage sag that will occur in a facility.

Andreas Eberhard is member of various power quality standard committees around the world. Over 10 years of experience in product compliance based on international standards. He is Vice President of Technical Services at Power Standard Labs and can be contacted at aeberhard@powerstandards.com, or Tel ++1-510-522-4400.