A team of scientists from the University of Texas at El Paso have developed a way to control electromagnetic waves in three-dimensional space using plastic metamaterials created with a 3-D printer.

“When you fold electromagnetics into three dimensions, the components interfere with one another, and it becomes a confusing electromagnetic mess where nothing will work—like when a lightning storm produces static while you’re listening to an AM radio station,” Raymond Rumpf, Ph.D., director of the EM Lab and an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Texas at El Paso, said. “We have figured out how to control the fields and flow the waves so that there is no interference.”

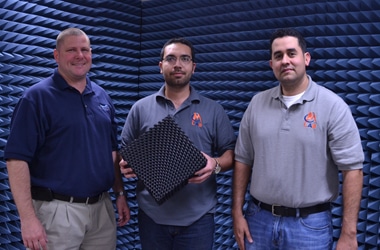

With assistance from Javier Pazos and Cesar R. Garcia, electrical and computer engineering Ph.D. candidates, the research team printed a complex geometrical lattice able to manipulate the electromagnetic near-fields surrounding electronic devices. The metamaterial was created using inexpensive plastic, which allowed the researchers to keep productions costs low and avoid energy loss typical of many metal metamaterials. The new technology could help lift restrictions on device size by preventing unwanted signal interaction between electronic components placed close to one another.

Research results are published in the journal Progress in Electromagnetics Research (PIER).

Invented in 1984, three-dimensional printing, or additive manufacturing, is the process of creating a solid 3-D object of relatively any shape or size from a digital model. In recent years, 3-D printing has been viewed as a boon to certain industries where a method for quicker, simpler mass production could be beneficial. Earlier this year, NASA announced a custom 3-D printer capable of creating tools and replacement parts for astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) had been flight certified.

“I am convinced that 3-D printing is going to revolutionize manufacturing, and electromagnetics is going to be very 3-D in the coming decades,” Rumpf said, adding that continued use of 3-D printing may lead to circuit boards becoming 3-D instead of 2-D, “so we’re going to need to know how to control the waves in 3-D.”