The opportunities for test labs are huge in the dynamic markets of Asia.

Mike Violette, Washington Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA

INTRODUCTION

There are various reasons to consider expansion into international markets. Factors that force companies to look across the border or across the ocean include obvious opportunities for product and/or service offerings, changing or shrinking domestic markets, and a need to “follow the customer.” The current global economy is settling into a new paradigm. Will U.S. laboratories be ready to greet international opportunities?

This article outlines some of the trends in developing markets, based on observations of the unwinding of the compliance market in Asia.

The development of laboratory opportunities tracks the development of economies, markets, and ultimately, technology. Economic development proceeds from an agrarian-based society to a low-tech manufacturing, and then to more sophisticated forms of manufacturing.

This progression drives the development of new technologies. As markets expand, the requirement and demand for standards pushes organizations to develop harmonized approaches for producing goods. This development, in due course, creates demands for evaluation of those products to determine conformance with the standards. Therein blossom opportunities for independent test labs.

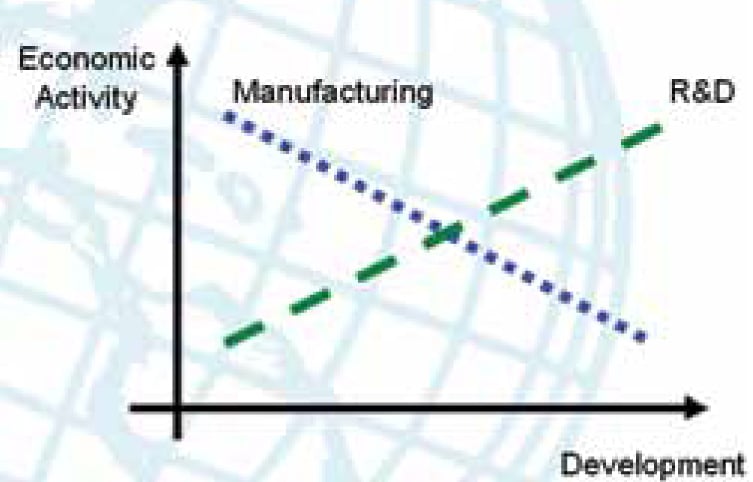

There is an inherent balance, of sorts, between manufacturing and research and development (R&D). Historically, when an economy has a lot of manufacturing, the R&D expenditures remain relatively low. The explanation for this phenomenon is that outside interests have brought in the technology to take advantage of low labor rates and to develop manufacturing capability. This often-repeated scenario has shaped the economic relationship between the U.S. and Japan and the U.S. and China over the past 30 years. The following graph (Figure 1) depicts this inverse trend. As a function of the level of development, the more an economy matures (and becomes more complex), manufacturing will account for a lower percent of economic activity. Conversely, the general trend is that the amount of R&D will increase with economic development.

These changes have been a major factor in the relationship between Taiwan and China. In the last 10 years, much of the manufacturing has shifted from Taiwan to the Peoples Republic of China. Taiwan retains its leadership role in developing the technologies that are used in China. But that paradigm will not remain fixed for very long. Chinese technologies are developing rapidly. The question becomes: what will Taiwan (or the U.S., for that matter) do in the future. The answer is simple: embrace the change and focus on innovation.

WHEREFORE ART THOU, STANDARDS?

For developing nations, the experience of the United States (and the Western World) over the last 200 years has essentially been compressed and impressed upon developing countries as they transition from agriculture-based markets to consumer (and, later service-based) economies. The rise in standards of living makes goods more available and the demands for consistent supply of those goods creates the need to evaluate/regulate the processes of creating these products and delivering them to the consumer. Who, then, is charged with assuring that the processes are sound and that confidence in the product is assured? It is really a collaboration of several entities, with the government assuming various roles in the supply and delivery chain.

The Western World has developed a system of accreditations and certifications that is supposed to keep the system working and in balance. The governments, usually under the ministries of trade or commerce departments, maintain an oversight position that, even in the relatively-advanced United States, is admittedly uneven and not uniform across the various agencies charged with ensuring free trade while protecting the citizenry. In the West, the testing and evaluation of products is an open process wherein private laboratories compete for business based on a mix of capabilities and required accreditations.

In the food business, this is called “Farm to Fork” wherein the process is (supposedly) vetted at various stages by a combination of internal validation and external auditing. A slip-up occurs when malfeasance or worse is at play, such as the recent problems manifest in the salmonella-tainted peanut butter paste. In these cases, internal labs were (apparently) patently ignored. As this article is being prepared, criminal charges are pending, and Congress is considering legislation that would make it illegal for an inspector to be employed by the food company under inspection. (From our experience, it is unfortunate that sub-standard testing and the duplicity of some Asia entities have put U.S./Asian trade on a suspicious footing.)

In developing countries, the trend has been to adopt centralized control over the testing of products and, over time, allowing the system to evolve to an open-market based one. Of course, this creates an unfair, some might say, unreasonable approach in some of the developing countries because no one is allowed to compete with government labs. However, this process does not seem so unreasonable when it is viewed as one step in the inevitable evolution of product conformity testing. Ultimately, the situation changes as the market expands and as confidence builds in the local technical and regulatory environment—a process exemplified by developments in Taiwan.

THE EXAMPLE OF TAIWAN

In the late 1980s, as the personal computer business was gaining speed, the requirement for the development of local testing capability was the province of the Taiwan government. It was a matter of practicality (as no other entities with the resources for establishing testing laboratories existed in the country). Still, these first test facilities put in motion an evolution in test sophistication that was, in a not-insignificant way, the result of government control. Taiwan’s martial law, or as it was termed: “Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion” is one of the more fascinating chapters in Twentieth Century history. Martial law was in effect from 1947 to 1987, a period of forty years. It was not until the country had gained sufficient economic stability and prosperity that martial law was lifted and democratic processes were put in place. The first democratically-held elections were held in 1992.

What does this have to do with testing? Well, testing often reveals bad news—and may force product recalls, product introduction delays, and other unpalatable effects. Only a stable society can collectively accept bad news (such as product testing failures) and muster the critical self-examination that leads to positive change. Thus, in Taiwan, several things happened over a very short period of time. The country evolved from an agrarian-based society in the 1950s to a low-value manufacturer in the 1960s and 1970s, and then to a sophisticated producer of world-class technology—all in the span of about 30 years. Currently, over 30 independent test labs operate in Taiwan, each competing (quite aggressively) for market share with the capabilities of many of these labs rivaling any in the world.

As previously noted, China is on the same track and, while hard-liners probably would not admit it, is following Taiwan’s lead in many ways, but with the compression of process and technology development arguably outpacing anything that has happened anywhere at anytime in history.

Taiwan is used as an example because it has matured to the point where it has agreements on standards and conformance that allows for the mutual exchange of data and test results between Taiwan and the U.S. (and other economies). It is difficult to predict the way that China will evolve, but given the track record of developing economies and, barring some calamitous political or societal earthquake, China’s present system will open up as well. For some product sectors (safety and radio frequency law), the government is the sole provider of final testing and approvals. In addition to the natural evolution of open(ing) systems, these barriers are being eroded by requirements under the World Trade Organization (WTO) accords that require that various institutions and processes be opened and that access and competition be allowed. (Product certification is one example, while banking and insurance are others.)

THE ASEAN REGION

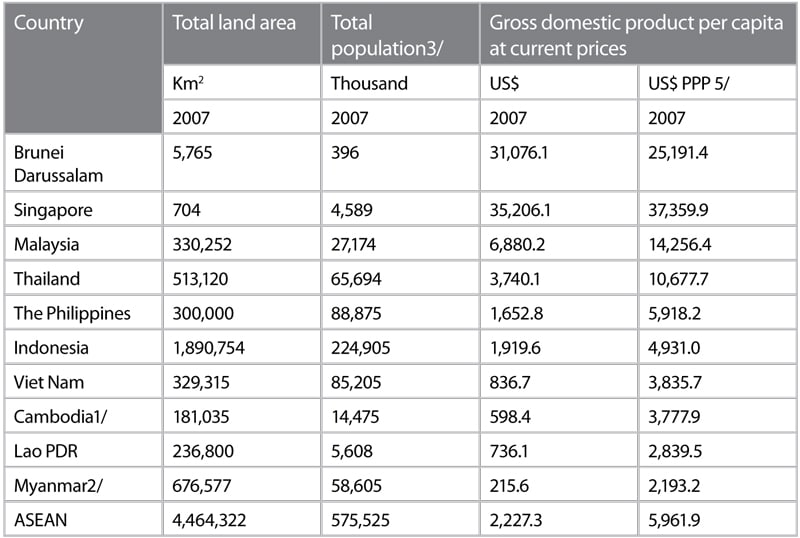

Looking beyond the examples of China and Taiwan (Japan and South Korea are also fine examples of the above-described evolution), if a lab is looking at expansion opportunities, it may indeed find them in the countries of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). The ASEAN group is composed of the following countries: Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam with a combined population of 570 million people.

The levels of development across the ASEAN group are as varied as the countries are culturally. At the top of the economic ladder is Singapore, a vibrant port and a beacon of prosperity— modern in every sense of the word and with a GDP (gross domestic product), based on purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita of over $25,000 (2007). On the bottom rung is the dysfunctional Myanmar with a GDP per capita of about $2200. Vietnam, emerging as a fast horse in the development race is a step higher, with a GDP (PPP) of around $3800.

Its position on the economic scale generally tracks a country’s sophistication in product testing and conformity assessment development. For example, few to no conformity assessment systems are to be found in places where development is not sufficiently advanced. To set up a laboratory (or to do business in general) is going to require “creative” arrangements.

The Asia-Pacific region market (which is wider than ASEAN) includes the 21 economies of Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, China, Chinese Taipei, Hong Kong-China, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Mexico, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Singapore, Thailand, United States, and Vietnam. In the compliance testing industry, Singapore, Japan, and Taiwan are the most “developed” in terms of standards and functional mutual recognition arrangements because of several key factors, including the cultural and business evolution and the development of these nations as technology-based markets.

That is not to say that the other countries do not have a developed testing infrastructure. A simple index is found by perusing the Test Site listings on the FCC web site. Certainly, Japan is at the apex of the testing infrastructure development although as developed as Japan is, there is still not a truly “open” process for placing products on the Japanese market. At the time of this writing, however, Japan and the U.S. are currently working through the details of a Mutual Recognition Agreement that would allow U.S. Certification Bodies to certify for the Japanese market.

SO WHAT ABOUT THE OPPORTUNITIES?

With the past as prologue, laboratories looking for the next opportunity are likely to look at a few key issues and, in most cases, be ready for the long haul. The critical factors in making an assessment and developing a plan are:

1. Condition of market maturity.

2. Economic track, i.e., how is the country

developing. WTO membership is

an important factor because of the

requirement to create transparent

standards and conformity assessment

systems.

3. Political stability.

4. Physical location.

5. Per capita income.

When all this is factored together, an assessment can be made as to the short- and medium-term strategy for developing the testing market. My bet is on some of the ASEAN countries. If you view the flow of manufacturing, much of it is moving into the lower cost countries. Granted, much of this is “low tech” at this point, but if history gives us an example, the technologies will eventually flow into these developing countries.

The question becomes which country. A piece of the economic part of the solution can be derived from a summary of simple statistics of the ASEAN countries.

At the top of the heap, in terms of GDP is Brunei Darussalem. This country, however, is a sultanate based on oil revenues. I would cross that one off any list. The population is tiny at less than 400,000 souls. Singapore, as mentioned before, is certainly well-advanced, but expensive. The countries at the bottom of the list are affordable, but probably out of consideration because of overwhelming societal complications. Things can be too cheap. Indonesia, while sitting in the middle of the economic pack probably fails the political litmus test at this time. The interesting group is probably somewhere in the middle of the list: Malaysia, The Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand.

CONCLUSION

There are many other factors to explore, including corporate will to engage and to make the investment of time and money. The lesson that can be taken away, after observing what has happened in the dynamic markets of Asia is that the opportunities are huge, if a balance between informed conservatism and risk can be struck. The only real way to figure it out, once the pack is narrowed, is to sit on a plane for 16 hours and to find out for yourself.