Government agencies are scrambling to find a solution for ongoing interference that could prevent a maritime vessel in distress from calling for help.

Weather alerts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration are bleeding into the maritime search-and-rescue channel used by the U.S. Coast Guard, disrupting and possibly blocking distress calls from maritime vessels, reports the Wall Street Journal.

The issue was identified last July, after a Coast Guard official concerned about an approaching squall line asked the National Weather Service to stop issuing tornado warnings because they were interrupting chatter on Channel 16, the international maritime distress frequency. The Weather Service, concerned about tornadoes in neighboring New Jersey, declined.

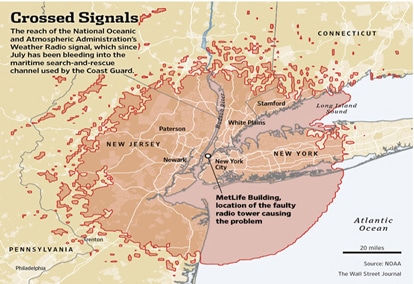

The affected area includes New York Harbor and parts of the Long Island Sound, which are heavily frequented by pleasure boats in the warmer months. Commercial fishermen also work in the area year-round.

The ongoing interference forces both agencies to make decisions regarding which emergency channel— the National Weather Service radio or maritime Channel 16—deserves priority in dangerous conditions.

“It puts two agencies with similar missions in a very difficult situation,” Ross Dickman, meteorologist-in-charge at the National Weather Service in New York, said.

“Our mission is the protection of lives and property. When you’ve got a situation such as a severe thunderstorm squall line going through the area, if we have to turn our transmitter off, we’re not meeting that mission. If we do turn it on it goes against their mission of search and rescue.”

In an effort to minimize the interference, the New York City weather radio, instead of operating continuously as it has done in the past, is used only to issue “short-fuse” alerts about life-threatening phenomenon such as tornadoes, severe storms or flash floods. Coast Guard officials have also developed a “workaround”—to monitor Channel 16 and notify the Weather Service as soon as the emergency alerts begin to bleed into the emergency maritime channel so that the weather agency can disable the transmitters.

The Weather Service is hoping a plan to move its antenna from atop the MetLife building in midtown Manhattan will yield a more permanent solution. The process is expected to take up to six months.